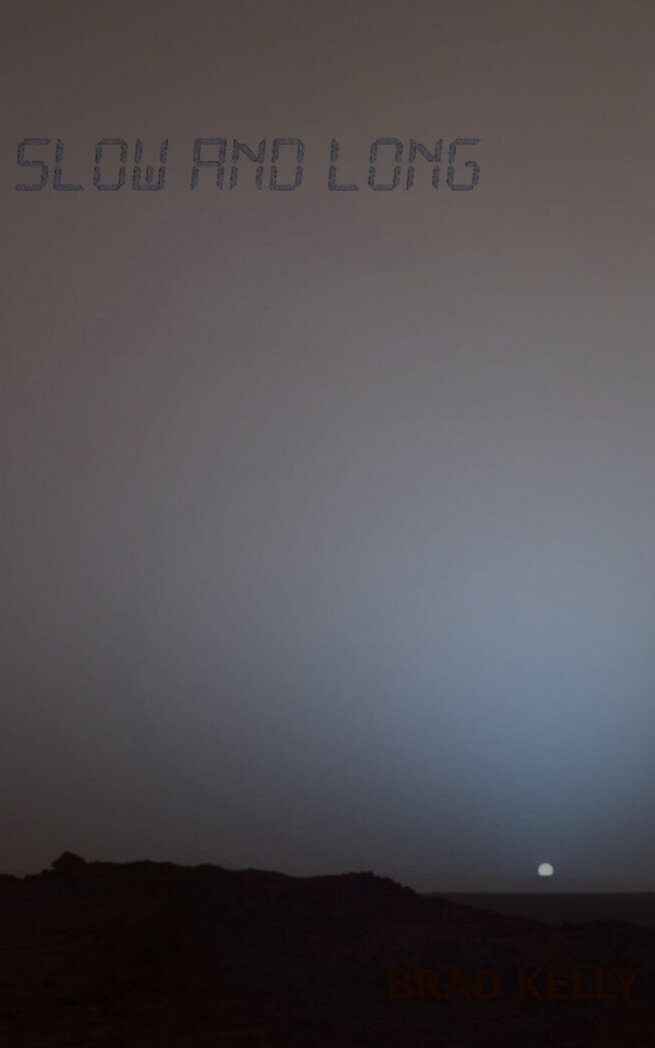

Slow and Long

Listen to the audio version

[] Kali, the Goddess of Destruction and Change. He might as well believe in her; he has the time. Kali’s role in all this, among other things, is to obliviate you. And after you are stretched and smashed by the inevitable gravity of her black hole, you reconstitute dripping with the epiphany that nothing she has killed ever mattered, that all the things you were and wanted existed as mere illusion. He thinks the slow and long is how she works him and he waits for the realization. They say she is also the Goddess of Time.

It’s hard to remember now, but Chip used to have fantastic dreams: buildings the height of mountains and mountains straining to poke their icy crowns into outerspace, blackwater swamps teeming with prehistoric life, holes in the earth that could carry him clean through to the other side, abandoned highways cutting some cursive protest to the cosmos in letters a thousand miles tall . . . But he never quite found these, out in the world, and Morgan said it was because he never sought them. One has to look in order to see just as one has to sleep in order to dream.

[] Chip and the rest of the Odyssey team rode up in the luxury suite of the Space Elevator, rockets seeming by then as primitive as starting fires by rubbing sticks or producing children through the old birth canal. They signed their last waivers and ate their last Earth meals [for Chip a double-cheeseburger and a chocolate shake] and made final amendments to their 216 cubic foot pods of belongings. There were not families to say goodbye to — that was part of the deal — but the crew had become Chip’s closest friends. They spent a year training cooperatively after a year surviving through the selection process together. Of course, this was a different Chip. The team had been hand selected and then painstakingly shaped into the men and women they were now. Still, Chip wished Morgan had been there to see him off. No one else had stuck. There was a lacuna in his heart — not a hole as he’d heard it described. It seemed the thing was there, he’d seen it, but couldn’t find it again in the few places he’d looked. He wanted Diogenes the real dog, at the very least, down there in the media pit as they climbed aboard. Someone said it was good to be nervous, that a whole new genre of nervousness was being invented as they rode the Elevator up.

One of the fifteen backed out a second before they gave her the needle — an insectoid spike slid icy cold into the spine. Later, she’d be interviewed with awe like those who’d decided to forfeit their tickets aboard your Titanic or Flight 93. Between the shot in the Elevator and the docking on the ship, six more died of aneurysm, seizing and vomiting blood without the grace of gravity. And, by the time the mission was aborted — minutes, really — three more were dead, and before anyone could blurt out an explanation or analyze any data, it was just Chip and the team of scientists now pulling their hair and ignoring the klaxon of incoming messages, as they engaged for the descent. Time moved faster, gaining speed as they fell. Chip would only remember watching through the lucite floor as the Earth grew beneath them.

[] Hundreds of years later, the sun hangs gauzy in the pollution and the city down below him has swelled and glitched its way up into the valley he overlooks. Close enough that people are visible through his looking glass, flitting diodes on the board, hive insects on the streets and riverwalk. The river, now, ink-black with grime. When Chip read history, he saw that this was nothing if not inevitable. Every moment predicted the next and if you squinted in just the right light you could sometimes see where it was all going.

He remembers his University years in flipping still-frames. In those days, you either accomplished something at 20 or flopped out of your wasted Rummaspringa at 30 into the larger gigconomy, assembling meals for people or panning for figurative gold in the web’s literal stream. Science declared that nothing was going to ever run out, so the only commodity left was smiles and these they sold to each other gewgaws. Chip, in contemptus saeculi, took up school to live near the barren mountains and read books and see if he could find anyone else that might run the middle path. Though he was apocalyptic, he was not cynical. Things were simply coming to an end and he wanted to know the vast history of everyone before it was over. In those books, in the tides of well-sourced facts, he thought he’d be able to live outside of time, feel it pass by out near the skyline, far enough away that the ground might stay stable under his feet.

Morgan in their junior year and the summer together on this mountainside. Some other mountainside. Reading for hours in hammocks with their chores done. Making glitchy music on the unvarnished floor. Eating apples from just past their doorstep and hiking in the dew twilight of morning wading in. They crafted a kaleidoscopic thing out of glass and old computer parts to hang in their tree and make of the sunset something purple and Cubist and new. Laughing and Morgan dancing barefoot in the veiled light, a white linen dervish , the gems of her teeth flashed at him in the rhythm of everything.

[] There was a plan for interstellar flight that included sending people as data to be reconstituted out at one of the exoplanets. It turned out a person’s brain could be transliterated into 1s and 0s and these fed into semi-biotic machines wholly accurate down to each pixel of memory and tic of psyche. But, much to the collective chagrin, during the femtoseconds a consciousness compiled in the neuroserver, the translated personality lost all concern for anything. Enlightenment, of a sort, gone radiant in a few plancks of true detachment. This new Boddhisattva in the machine could not be convinced to take up any task at all. Could not speak but in Ohm-like aphorisms that sent young technicians running up the side of mountains never to be seen again. It wasn’t going to work. There’d be no faxing ourselves into the great beyond. And yet, science said someone had to be sent to Vega and beyond. Out of the solar system and into the sidereal emulsion of the Milky Way. It was always going to happen.

Already, normal, Internet-surfing type people were living to 120 years old. A more direct plying of one’s genes promised uncharted ages for the generation coming up. Two hundred and fifty years was somehow estimated. This stretched the Odyssey Mission to two centuries, by our lights, but all the warp drives fantasized about never materialized. They’d have to travel at one-half c at best. Some committed Engineers came at it from the other side: they learned how to slow down time in the extreme locality of one’s body. To fold proteins and stoke mitochondrial fires such that a day passed before Chip’s eyes and through his physiology in what felt like an hour. It would have worked, too, the researchers pled in court, but no one had thought to test the process’s efficacy in the depleted G of the Space Elevator’s luxury suite. It was decided that Chip, who’d survived and proven the theory, would hurt their defense, waste everyone’s time, that he was a casualty of dreaming too big.

[] After the summer of the cottage, Chip lost track of who they were supposed to be down in the city. Come September, Morgan wandered down the path by herself, looking back three times and he always hoped a fourth he didn’t see. She visited for parts of the harsh, old fashioned winter, rubbed the new wood-chopping calluses on his palms and twisted the ends of his new beard. She said she wanted that life but there were other trajectories down there. Equations that found her coordinates in the irrefutable graph of space and capital t Time.

Her next summer on the hill was only two weeks. The cycle of every day swelling valences of beautiful until the afternoon she abruptly left — as though she’d been filling a reservoir until she was safe to cut loose. She had prospects with some muckety mucks and a respectable fortune smeared out over the next few decades. Chip could offer nothing to match. She said she’d miss their sunsets and he said he’d keep an eye on them.

“You’ll be lonely up here, won’t you?” she said. They lie in their hammocks strung up in the old pine, twisting slightly in a warm breeze as dusk settled in. “It’s beautiful, all this, but . . .”

“People have had it lonelier.”

“At night, though. When it’s quiet.”

“It’s not a desert island. I can talk to people whenever I want. I can talk to you.”

She wanted him to come down the mountain, but she wanted him to stay, too. Understood he needed to somehow better than Chip himself. She spoke transparently of the pitfalls, knowing he’d see her true intent and she wouldn’t have to say a word about wanting him in the city with her. He could be snowed in, he could sink the axhead into his calf muscle, impale himself on a broken sapling, wake up with a brain tumor. She was giving him ways out but he felt he’d talked himself into all of this.

“The years coming up,” he said. “They’re going to be weird, aren’t they?”

“They all have been so far.”

“I mean without each other. Lives are going to go on.”

“Yeah.”

They couldn’t see each other the way they lied there suspended. There are things past eye contact, though, and Chip could feel the slightest whisper of her gravity pulling them together.

“Will you visit the city?” she said.

“Supply run every few weeks.”

“Yeah.”

“You think you’ll come up here ever?”

“I don’t know.”

[] At 25, Chip was teaching NeoYoga to a few Communists down the creek in exchange for carbon fiber shipping cartons and ancient wireless phones and fossilized toothpaste from the old illegal dump on the other side of the hill. This he sold as antique trash on the web, everything now squelched down into fuel. The pieces went mantel-wise in swank apartments in the city, served as conversation pieces bolted to the wall or centered on the dining table. He knew the city now, too, Winters he’d couch around in those apartments, carousing as was considered enlightened in a fashionable way, quoting from history to charm free meals, saying something wise once or twice over wine and holographic cigarettes. Most nights, though, were as lonely as sleeping a mile off from the oasis, looking down on it from some wind-sheared vantage point. There was a proof in the New Math that the universe was made up of loneliness.

Chip took in a stray dog so gray it was nearly blue and he named it Diogenes and, watching it perambulate the premises, he came to think the dog did, in fact, know some secret philosophy. Satisfied by the humblest pleasures, taking his times of rest and times of play as they occurred to him, rolling in the dirt and dead leaves regardless, bursting through the same scrubby bush time and again.

He read every book he could. Most of these were history and after awhile he could contain. He could analogize every situation to a battle in a foreign land, the emergence of some notion, or the spread of a disease; he could describe with detail all the big corporate mergers and the fall of Rome and the communication ecology of the pre-Internet world. He knew about jungle empires in the Amazon, rogue avalanches and typhoons, every revival, renaissance, and religion. The unwritten wars known only by their potsherds and skeletons. But soon enough new facts pushed out the old to make room and he felt a tangle of things he no longer knew like silty mud at his feet. Somewhere the project had failed.

He thought up ways to return to the city and looked for jobs only to find himself skill-less and unconnected. He saw thirty years ahead, living as an unkempt caretaker somewhere, the overstuffed encyclopedia of his head a core eccentricity, and his bachelorhood a mild affliction that might score him a free meal now and then. He took down the hammocks. He patted Diogenes’ head and worried.

[] One day, Chip saw the open posting for the Odyssey Mission. He had to be able-bodied, intelligent, and of around his age. An enthusiasm for space travel was a must, as was the ability to commit to a mission. He had to be willing, most importantly, to never see Earth again. He would glimpse Mars and pass Neptune and, in twenty years time, they’d reach the first exoplanet, retrieve a supply-laden rover and send it rocketing deeper into the abyss. This they’d follow for the rest of their lives. A single, gadgeted tendril of humanity out there in the nothing, every few years brushing up against islands of black rock raked bare by solar winds, messages to and from the Earth growing so laggy that the many pasts would be indistinguishable, so far away that everything Chip knew could be covered up by a thumbnail.

To find the crew, a selection pool was broken down and training began on those who remained. They looked for rapport and flexibility as much as education and generativity in the curriculum vitae. It seemed as random as a blood test or fifty years toiling at a single job. Chip briefly considered each level he cleared a kind of typo in the events — it hardly crossed his mind that he might go.

Almost a million signed up. Half of these were eliminated by background checks or infoscans or algorithms, another quarter via Myers-Briggs in several filters. Also: the computer literacy test, web interview, physical, second interview. Month co-habitation with three selectees and one wildcard in a former college dorm. A two hour session of Jungian hypnosis. Space Elevator to test gravity sensitivity. Bake sale. Sensory deprivation. Cohabitation for three months with a dozen selectees and three wildcards. Interviews. Talent show. Interviews. Ropes course. Cohabitation with thirty selectees, half to be eliminated, plus five wild cards and one actual psychopath off his neuronal supplements. It was exhaustive, challenging, and yet the best way through was to merely be yourself.

Chip out of this, somehow. His knowledge of History won him Conversation points and his affability found him well-fit to the various Irritation Matrices. But there was also Rita, who he liked, and Chet. Marcus who was teaching him the next level in his chess game with an infinity to master it. Xian who would trade grappling lessons for those in yoga. Anat who played almost every instrument and shot him priceless smiles . . . it was going to be kind of wonderful out there. He started to feel that this might mark his place history somewhere — though he remained wary of stroking his ego. It was an event that seemed to mean something, that had little cedent, pre- or ante-.

[] A day gone by in an hour to wile away years supposedly lucky. Debrief and shocked faces and sweaty lunchmeat with jalapeno aioli and claims he was catatonic that he vigorously shook his head at. A press conference that required the entire hour of him to ask for another sandwich and make the portentous statement: “The point was to never come back.” And, before they became embarrassed of him: “I’m not sure that I have.”

[] It took nearly two of his days before interest in Chip died away and he was transported somehow to a/the cottage. Details were slippery then and he squinted often at spaces of nothing to keep things from moving for long enough to count. It was evidence of his erraticness. Voices came at him too fast to quite decipher, but much could be read by the way they stared at him, waved their hands in front of his eyes for the briefest instants. People in groups of more than two was nauseating and anxious, strobes of activity that made him dizzy. He only knew that he was to be taken care of and left alone, as he managed to ask for on a piece of paper over five long minutes.

A year soon passed (just over fifteen days by his lights) growing accustomed out in the cottage. He learned he could not watch screens, the time-differential turned them into a glitchy, perforated mess. And reading a book might take an entire season. But he’d get used to this. Learn how to sleep, how to let the days slip by, knowing there were to be so very many of them.

[] There was a message from Morgan asking if she could come visit, but he hesitated in response and two years passed and she lived in the fast time. She was married when he responded, taught Economics at a school for boys and railed against science for ruining him. She implied that his brain damage was a tragedy. He wrote that he was simply living in the slow and long.

[] The only things that moved slow enough to watch were the foliage as fall became winter and winter became spring. And storms. The sky. He’d watch the sun and its attendant clouds traverse, and then he’d feel it under and behind him passing across the rest of the world, the stars cranking into place pulling their laser-like trails. When his calendar clicked into the next day, there was an instant of stillness. A period between sentences to take a breath. And then he could feel the sun coming back round the other side and see the night sky swallowed up by that growing blue. He spent much of his time watching the sky. Sitting on the bald hill in his blue and orange jumpsuit threaded to last a thousand years.

Every hour of his a day. Every year twenty four years. And he was to have a hundred more of these.

In dreams, this was not true. In dreams, vases fell at the old 9.8 meters per second squared. The figures moved at his pace and seemed none bothered by it. He dreamt sometimes of being in space, by now well past the sun’s effect. And he dreamt of dogs fetching slobbery sticks down the hillside, or that she’d stayed another summer and in that summer he taught her to chop wood and she taught him to read tarot, and in those dreams he had no recall from the vast tomes of history and he knew in all instances that not one particulate moment was repeated. And, by this very fact, because of it, Everything must be.

At times, he felt boredom as acute as liver failure. A kind of boredom they’d vaccinate for if it leaked into the groundwater. It became a game to focus on the present looking for a single tractable instant in which nothing happened. To find glass shards of stillness. And sometimes from these three or four moments in a sun cycle, he could almost patch the still frames together and remember what a day used to be:

A day began in bed with her and drifted along the smell of coffee into a metronomic thrum of work tinged with sweat. And it all coalesced into warm meals tidy in his stomach, an afternoon sweltering hammock-wise in the bliss. And the pleasantly dull night, sometimes, being there until the sun came cranking around again. In his points of stillness now, he can see the after-image of those days and he takes a self-satisfied inhalation as he looks up at the sky.

[] A very old woman came to see him, her face as familiar as those on the old coins. She moved almost as slowly as he, wore matronly clothes and a doctor’s mask over her face, and it took a long time but he promised her that the air was cleaner up there and she showed him pearl-like teeth.

She stayed with him for hours, half of it sleeping noiselessly as a bird. They talked of the city and this led to talking of anything but. He listened and spoke in only single words: Long. Dog. Alone. Sunset. Sunrise. Music, with a question mark. “Thousands,” he said. “Years,” he said later.

She hung a jumbled pane of colored glass over the sun as it set and, after, she squeezed his hand for the width of an instant. She spoke a little parable about being old, about having regrets. She said that she was ready to go.

Word came later that she’d passed. He spent the spring considering a trip down into the city to watch her casket descend. From a distance, that was the plan, hidden beside a tree and under an umbrella. He didn’t go. He sat and watched the grass of his slope grow long and go to seed. There weren’t thoughts any longer, the way he once thought of thoughts. He had only instants he could cling to and those that shuttled on by.

[] He was not as separate from it all as he believed. A final supply shipment arrived and it was as much cobwebs as it was instant beans and freeze-dried gruel. Chip sat on the hill eating the final bag of chips; the irony was not lost on him. It seemed nothing if not inevitable.

He watched the first bricks fall, down there. The ecstatic neon go dull, a gradual tide of winked-out lights crawling slow over the city. He watched their sky go streakless and their moon fat and unheeded overhead. The coal grey vein of their rivers run clean. A brassy thickness like rust over everything, left behind by the clearing haze. He watched through a looking glass as the streets ran clear, like rinsing the blood from a wound. He ate the final crumbs, hard as tiny stones, after picking them from his beard.

Kali, frenzied dancer and Goddess of Time. She does not answer prayers and all that can be offered to her is blood. He wonders how much will be enough. He wonders if, somehow, this is all enlightenment and he just hasn’t noticed. Or maybe it’s all over and this is what happens after. He lies down in the itch of long grass to watch the sun fall through the lens Morgan has made. They say she is the Goddess of Destruction and of Change.

Listen to the audio version: